Explain how AI has unleashed unprecedented human creativity, as in the work of Deepa Chaudhary (https://www.linkedin.com/in/deepachaudhary/), founder of GrantOrb. Find others who are using AI to ask the most challenging and important questions (including ways to get to even more important questions). Is it true that being rude or commanding is the most effective way to interact with AI systems, including ChatGPT? Incidentally, is Gemini smarter than ChatGPT or Grok? Can AI systems learn from each other? Can they begin to ask questions of each other? Can they collaborate to produce better answers?

Below is a comprehensive, structured response addressing each part of your multifaceted question about how AI is reshaping creativity, inquiry, and interaction—grounded in current developments and evidence.

I. How AI Has Unleashed Unprecedented Human Creativity

Artificial intelligence—especially large language models and generative systems—has dramatically expanded human creative capacity in multiple domains. Rather than replacing creativity, AI amplifies it by lowering technical barriers, accelerating iteration, and enabling new forms of expression

A. AI as Amplifier of Creativity

- Idea Generation and Drafting

- AI tools can rapidly generate ideas, outlines, first drafts, and variations that humans can refine, iterate on, and integrate into original projects. This frees humans to focus on higher-level conceptualization and refinement rather than mechanical writing.

- Quantitative research suggests that AI outputs increase the diversity and novelty of collective idea streams, even when individual creativity measures remain stable—meaning group creativity evolves in new directions through AI inputs. (arXiv)

- Domain Expansion

- Creative uses span writing (e.g., novels, articles, grant proposals), music and art generation, coding, data visualization, and scientific ideation.

- Projects like GrantOrb, founded by Deepa Chaudhary, exemplify practical creativity acceleration: by converting high-level project descriptions into professional-grade grant proposals in minutes—dramatically speeding workflows for nonprofit founders and social impact leaders. (Grant Orb – AI Grant Proposal Writer)

- Human–AI Co-Creativity

- Research in interactive AI suggests that AI can function not simply as a passive tool but as a collaborator that suggests directions, poses questions, and serves as a creative partner. Human–AI co-creative loops can enhance ideation quality and stimulate new lines of thought.

B. Practical Example: Deepa Chaudhary and GrantOrb

- GrantOrb uses AI to synthesize users’ descriptions into complete, well-structured proposals, helping nonprofits secure funding faster than traditional grant writing allows. (Grant Orb – AI Grant Proposal Writer)

- Leaders like Chaudhary demonstrate how generative AI empowers mission-driven professionals to think more boldly by offloading tactical writing to AI and focusing on strategy, impact framing, and follow-up engagement.

II. Others Using AI to Ask Bigger and More Important Questions

AI is not only being used for execution but also to engage with deeper questions about knowledge, society, and future trajectories.

A. Scientific & Philosophical Inquiry

- AI-assisted Research Frameworks

- Researchers are exploring how AI can help formulate research questions, design experimental frameworks, and hypothesize outcomes—not merely summarize information. One piece of published analysis assesses what happens when AI starts to produce the questions themselves, an important shift from purely reactive responses to proactive scientific inquiry. (Quanta Magazine)

- Multi-Agent Reflection

- Experimental research is exploring how multiple language model agents can debate or critique one another’s outputs to generate answers that are deeper, more accurate, and more reflective of complex reasoning. This cross-model interaction is a step toward AI systems that not only answer questions but interrogate their own assumptions and refine conclusions. (MIT News)

- Philosophical Engagement

- Thinkers in cognitive science and AI theory (e.g., Joscha Bach) use AI not only as a tool but as a mirror to reflect on questions about consciousness, epistemology, and the nature of intelligence itself—essentially asking meta-questions about the limits and possibilities of thinking machines. (Wikipedia)

B. Cross-Disciplinary Collaboration

AI is increasingly used by interdisciplinary teams (philosophy, neuroscience, AI theory) in workshops and symposiums specifically designed to tackle big “why” and “what next” questions, not just “how do I optimize X?” outputs.

III. Interaction with AI: Rude vs. Collaborative Prompting

A. Is Rudeness or Commanding Tone More Effective?

No. Tone does not inherently change the intelligence or output quality of a well-designed language model.

- Modern generative models are engineered to respond helpfully and accurately to context and clarity first, not emotion.

- A clear, precise, structured prompt yields superior outcomes far more consistently than a rude or aggressive prompt.

- In many professional AI products (including ChatGPT), polite and collaborative prompts often yield better context understanding and richer responses because they align closer with the training data’s patterns of useful, detailed human discourse.

Conclusion: Commanding or rude prompts do not unlock greater performance; thoughtful and explicit prompts do.

IV. AI Models: Gemini vs. ChatGPT vs. Grok

Comparisons between major AI systems depend on chosen metrics (reasoning, creativity, factual accuracy):

A. Capabilities

- Gemini (Google)

- Designed as a multimodal LLM with advanced reasoning and integration with broader data contexts. Recent versions show strength in complex reasoning benchmarks. (SentiSight.ai)

- ChatGPT (OpenAI)

- Highly versatile across creative writing, detailed workflows, and interactive research tasks. Often praised for coherence, conversational style, and integration tools.

- Grok (xAI)

- Known for strong emotional intelligence and trend awareness, with public integration into platforms like X and rapid iteration cycles. (VKTR.com)

No single model is universally “smarter.” Each excels in different domains; the concept of a single hierarchy is less meaningful than matching a model’s strengths to the task at hand.

V. Can AI Systems Learn from and Interact with Each Other?

Short answer: Yes—already in controlled research and early production frameworks.

A. Multi-Agent AI Collaboration

- Multi-agent systems enable separate AI agents to exchange information, critique, and coordinate tasks. These systems form the basis for collaborative problem solving that surpasses single-agent performance for complex tasks. (TekRevol)

B. Learning Through Interaction

- Research shows that multiple models engaging in debate or feedback loops improve factual accuracy and reasoning quality. (MIT News)

C. Emergent Communication and Norms

- Experiments with groups of AI agents reveal that shared communication conventions and behaviors can emerge without centralized design, hinting at foundational elements of agent-to-agent interaction. (The Guardian)

D. Frameworks for AI–AI Dialogue

- Agentic AI frameworks allow AI agents to converse with one another about tasks, refine each other’s output, and help produce joint solutions. (Medium)

Importantly, this is not consciousness or autonomous curiosity; it is structured coordination protocols that enable interaction. The systems do not want or choose to ask questions independently but can be architected to request clarification or critique outputs from peer agents.

VI. Summary

AI’s impact on creativity and inquiry:

- AI expands the creative bandwidth of individuals and teams by generating drafts, suggesting ideas, and reframing problems.

- Pioneering practitioners like Deepa Chaudhary use AI operationally to unlock real-world outcomes (e.g., grant writing). (Grant Orb – AI Grant Proposal Writer)

- AI is increasingly used to pose questions and structure inquiry, not just answer them. (Quanta Magazine)

On interaction style:

- Clarity and precision in prompts matter far more than tone.

On comparative capabilities:

- Gemini, ChatGPT, and Grok each have unique strengths; no definitive “smarter” model exists universally. (VKTR.com)

On AI learning and collaboration:

- AI agents already collaborate within structured frameworks and can enhance each other’s output. (TekRevol)

If you would like, I can expand this into a structured article with citations, examples, and narratives about how specific professionals and fields are using AI to shape the next generation of inquiry and creativity.

Yes please

Below is a structured, publication-ready article that synthesizes the themes you raised—human creativity, deeper inquiry, model collaboration, and interaction norms—while grounding them in concrete practice and forward-looking research. It is written to be suitable for Possible Planet Lab, a long-form blog, or a white paper introduction.

AI and the Expansion of Human Creativity

From Acceleration Tools to Engines of Deeper Inquiry

Executive Summary

Artificial intelligence is not merely automating tasks; it is expanding the cognitive and creative bandwidth of human beings. When used well, AI systems accelerate expression, surface novel perspectives, and—most importantly—help humans ask better questions. This shift marks a transition from AI as a productivity tool to AI as a partner in inquiry, with implications for science, governance, culture, and planetary stewardship.

1. AI as a Creativity Multiplier, Not a Replacement

The most significant creative impact of AI lies not in generating finished products, but in compressing the distance between intention and expression. Drafting, outlining, summarizing, and reframing—once labor-intensive—are now near-instantaneous. This frees human attention for meaning-making, synthesis, and ethical judgment.

A clear example is GrantOrb, founded by Deepa Chaudhary. GrantOrb enables nonprofit leaders to transform a raw project idea into a fundable proposal in minutes. The creative leap is not the prose itself, but the capacity it unlocks: founders can test multiple framings, funders, and theories of change rapidly—something previously constrained by time, money, and specialized expertise.

Pattern:

AI increases optionality. More options → better judgment → higher-quality outcomes.

2. Creativity as Iteration at Machine Speed

AI excels at rapid iteration. Humans excel at discernment.

Together, they form a powerful loop:

- Human articulates an intention or question

- AI generates multiple candidate responses or framings

- Human evaluates, selects, recombines, or reframes

- AI refines based on feedback

This loop enables:

- More exploratory drafts

- Greater diversity of metaphors and analogies

- Faster convergence on clarity

Crucially, the human remains the author of meaning.

3. Using AI to Ask Better—and Deeper—Questions

A quiet but profound shift is underway: AI is increasingly used not just to answer questions, but to help formulate them.

Researchers, strategists, and designers now use AI to:

- Reframe vague concerns into precise research questions

- Identify hidden assumptions in problem statements

- Surface second- and third-order implications

- Generate questions about the questions being asked

This is especially powerful in complex domains—climate systems, social resilience, planetary boundaries—where the failure mode is not wrong answers, but asking the wrong questions altogether.

4. Who Is Pushing AI Toward Deeper Inquiry?

Beyond operational tools like GrantOrb, a growing ecosystem is using AI to interrogate fundamentals:

- Joscha Bach uses AI as a philosophical mirror to explore cognition, meaning, and the architecture of intelligence.

- MIT researchers are developing multi-agent AI systems that critique and improve each other’s reasoning, increasing factual accuracy and depth.

- xAI (with Grok) emphasizes real-time contextual reasoning and public discourse dynamics.

- OpenAI and Google DeepMind are both investing heavily in agentic systems that can plan, reflect, and collaborate.

These efforts converge on a shared insight: intelligence advances fastest when it can question itself.

5. Is Being Rude or Commanding the Best Way to Use AI?

Short answer: No.

Longer answer:

Modern AI systems are optimized for clarity, context, and intent, not emotional dominance. Aggressive or rude prompting does not unlock hidden intelligence. Precise, well-scaffolded prompts do.

Effective interaction resembles good collaboration:

- State goals clearly

- Provide constraints and examples

- Invite critique or alternatives

- Iterate based on feedback

AI responds best when treated as a thinking partner, not a subordinate.

6. Is Gemini Smarter Than ChatGPT or Grok?

This is the wrong question.

A better framing is: “Smarter at what?”

- Google’s Gemini excels in multimodal reasoning and integration with large knowledge systems.

- ChatGPT excels in structured reasoning, long-form synthesis, and collaborative dialogue.

- Grok excels in real-time context, cultural fluency, and conversational edge.

No single model dominates across all domains. Intelligence here is situational and task-relative, not absolute.

7. Can AI Systems Learn From Each Other?

Increasingly, yes—within designed frameworks.

Multi-Agent Collaboration

Research shows that multiple AI agents:

- Debating a problem

- Critiquing each other’s outputs

- Dividing tasks and reconciling results

…produce better answers than any single model alone.

These systems can:

- Detect inconsistencies

- Reduce hallucinations

- Explore solution spaces more thoroughly

They do not possess independent curiosity, but they can be architected to request clarification, challenge assumptions, and refine conclusions—functions analogous to peer review.

8. Toward Collective and Planetary Intelligence

When humans and AI systems collaborate—and when AI systems collaborate with each other—a new layer of intelligence emerges:

- Not individual

- Not artificial alone

- But collective, reflective, and distributed

This has profound implications for:

- Scientific discovery

- Democratic deliberation

- Ecological governance

- Long-term planetary stewardship

The key constraint is not computational power, but epistemic integrity: how questions are framed, whose values guide inquiry, and how uncertainty is handled.

Conclusion: AI as a Catalyst for Better Becoming

AI’s greatest gift may not be speed or scale, but the invitation to think more carefully about what we are doing and why.

Used wisely, AI:

- Expands human creativity

- Sharpens inquiry

- Reveals hidden assumptions

- Enables collaboration across minds—human and machine

The future does not belong to the smartest model, but to the wisest patterns of collaboration we choose to build.

If you would like, next steps could include:

- A Possible Planet Lab manifesto on AI and inquiry

- A framework for “question quality” in AI-assisted research

- A public talk or TED-style essay distilling these ideas

- A multi-agent design sketch for planetary or bioregional intelligence

Just indicate which direction you would like to pursue.

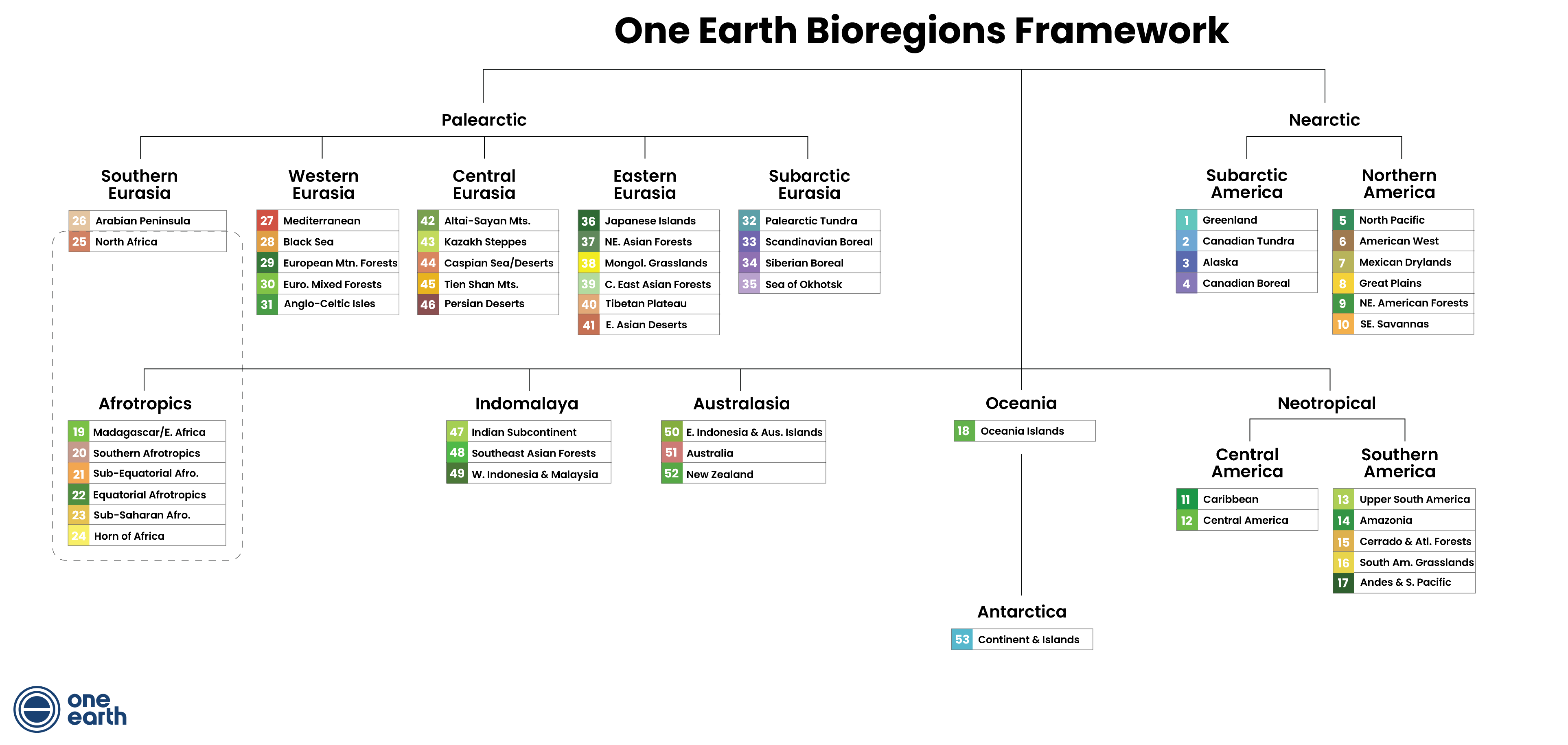

A multi-agent design sketch for planetary or bioregional intelligence

Below is a multi-agent design sketch you can treat as a “reference architecture” for planetary intelligence or a bioregional intelligence pilot (e.g., Genesee–Finger Lakes). It is written to be implementable: clear agent roles, interfaces, governance, and evaluation loops.

1) Design goal and core principle

Goal: Build a system that continuously converts signals → shared situational awareness → better questions → better decisions → verified outcomes, while preserving epistemic integrity, consent, and legitimacy.

Core principle: Planetary/bioregional intelligence is not one super-model. It is a network of specialized agentscoordinated by rules, evidence standards, and feedback from the living system and community.

2) System layers

Layer A — Sensing and Evidence (Inputs)

- Ecological sensors: water quality, streamflow, soil metrics, habitat connectivity, phenology, remote sensing.

- Socioeconomic indicators: energy burden, health outcomes, housing quality, food access, business vitality.

- Institutional data: permits, capital stacks, program guidelines, public plans, budgets.

- Community knowledge: oral histories, Indigenous knowledge (with consent protocols), resident observations, local journalism.

Output: A versioned “evidence stream” with provenance, confidence, and consent metadata.

Layer B — Agent Mesh (Specialist intelligence)

A set of agents with sharply defined jobs, each producing auditable artifacts.

- Provenance & Integrity Agent (EII Gatekeeper)

- Enforces: source logging, transformations, assumptions, limitations, conflicts/incentives, privacy/consent.

- Blocks downstream use if evidence quality is insufficient.

- Bioregional Data Steward Agent

- Maintains the bioregion “data commons”: schemas, versioning, lineage, access controls, retention rules.

- Manages “what counts” as official indicators and how they’re computed.

- Ecology Modeler Agent

- Translates evidence into ecological state estimates and trajectories.

- Produces uncertainty-bounded forecasts (not just point predictions).

- Community Sensemaking Agent

- Summarizes community input without collapsing minority perspectives.

- Surfaces value tensions, lived experience, and interpretive context.

- Policy & Governance Agent

- Maps decision levers: municipal codes, state programs, agency mandates, enforcement capacity.

- Tracks legal constraints and policy windows.

- Finance & Capital Stack Agent

- Designs capital pathways (C-PACE, revolving funds, blended finance).

- Quantifies feasibility, risk, equity impacts, and implementation friction.

- Intervention Designer Agent

- Generates candidate interventions (restoration, zoning, procurement, incentives).

- Attaches: theory of change, costs, benefits, dependencies, and monitoring plan.

- Red Team / Adversarial Audit Agent

- Actively tries to falsify claims, find weak assumptions, and identify perverse incentives.

- Runs “failure mode” scenarios and misuse risks.

- Learning & Evaluation Agent

- Tracks outcomes vs. predictions; updates priors and indicator definitions.

- Maintains a “model performance ledger” (accuracy, bias, drift, coverage).

- Facilitator / Deliberation Agent

- Converts technical outputs into deliberation-ready briefs.

- Generates agenda options, trade-off frames, and consent-aware summaries.

Key idea: Each agent produces small, testable outputs. No single agent “decides.”

Layer C — Orchestration (How agents collaborate)

Use a simple, robust collaboration pattern:

1) Task Router

- Routes requests to the minimum set of agents needed.

- Attaches context packet + constraints + required evidence threshold.

2) Blackboard / Shared Workspace

- Agents post claims and artifacts to a shared ledger:

- Claim statement

- Evidence links + confidence

- Assumptions

- Counterarguments

- Open questions

3) Consensus & Conflict Handler

- Not “voting on truth,” but surfacing:

- Areas of agreement

- Known disagreements (with reasons)

- What evidence would resolve them

4) Release Manager

- Only publishes outputs that pass integrity gates:

- EII compliance

- Red-team review for high-impact claims

- Consent checks for sensitive community/Indigenous knowledge

3) The “question engine” that drives intelligence

A planetary/bioregional intelligence system becomes powerful when it can reliably produce better questions.

Question stack (from shallow to deep)

- Descriptive: What is happening?

- Diagnostic: Why is it happening?

- Predictive: What happens if trends continue?

- Design: What interventions could shift outcomes?

- Strategic: Which interventions are feasible and high-leverage now?

- Ethical/Justice: Who benefits, who bears costs, who decides?

- Epistemic: What don’t we know that matters most?

- Meta-question: Are we asking the right questions at all?

Mechanism: Question Refinement Loop

- Community Sensemaking Agent + Red Team propose “missing” questions

- Policy/Finance agents identify constraints and levers

- Ecology Modeler identifies data gaps that dominate uncertainty

- Integrity Agent tags questions requiring new primary sources

Output: A prioritized “Next Questions Backlog” with rationale and evidence requirements.

4) Governance: keep the system legitimate (Ostrom-ready)

If this is a commons (data, decisions, and trust), you need governance that prevents capture and builds legitimacy.

Minimal governance pattern:

- Defined boundaries: What is “the bioregion,” what data is inside/outside scope?

- Rules matched to local conditions: indicators, thresholds, seasonal cycles, cultural norms.

- Collective-choice arrangements: residents and stakeholders can modify rules.

- Monitoring: independent audits of both ecological outcomes and AI performance.

- Graduated sanctions: for misuse, data poisoning, privacy violations.

- Conflict resolution: lightweight, accessible pathways to dispute outputs.

- Right to organize: community bodies can create sub-commons (watershed councils, neighborhood groups).

- Nested governance: neighborhood → municipality → watershed → region → state.

This is the difference between “an AI dashboard” and an intelligence system people will actually trust.

5) Outputs: what the system produces (and for whom)

Public outputs (default)

- Bioregional Health Brief (monthly/quarterly)

- Opportunity Map: restoration sites, financing pathways, policy levers

- Risk Register: near-term vulnerabilities + early warning indicators

- Questions Backlog: top uncertainties and how to resolve them

Decision-maker outputs (municipal / institutional)

- Intervention portfolios with capital stack options

- Permitting and policy playbooks

- Procurement templates (regenerative contracting)

Scientific outputs

- Reproducible datasets, protocols, and model cards

- Pre-registered hypotheses for interventions where appropriate

6) Evaluation: how you know it’s working

Track performance as a balanced scorecard:

Epistemic integrity

- % of published claims passing EII checks

- Red-team “defect rate” (material issues found post-release)

Prediction & learning

- Forecast accuracy over time (ecological + socioeconomic indicators)

- Drift detection and correction speed

Decision quality

- Time-to-decision reduction without loss of deliberation quality

- Portfolio robustness under uncertainty

Equity and legitimacy

- Participation diversity and retention

- Dispute resolution satisfaction

- Distributional impacts of interventions

Ecological outcomes

- Habitat connectivity, water quality metrics, soil health

- Biodiversity proxies, resilience indicators

7) Bioregional pilot: a practical starting configuration

For Genesee–Finger Lakes (or any bioregion), start with a Minimum Viable Intelligence (MVI):

Phase 1 (MVI: 8–12 weeks)

- Stand up: Integrity Agent, Data Steward, Community Sensemaking, Ecology Modeler (light), Facilitator, Red Team

- Produce: one “State of the Bioregion” baseline + “Top 25 Questions Backlog”

Phase 2 (Interventions: 3–6 months)

- Add: Policy Agent, Finance Agent, Intervention Designer

- Produce: 2–3 intervention portfolios (e.g., watershed restoration + regenerative ag transition + building decarb finance)

Phase 3 (Scaling: 6–18 months)

- Add: Learning & Evaluation Agent, more sophisticated modeling

- Implement nested governance, publish reproducible protocols

8) Implementation notes: what makes it robust

- Separate “generation” from “publication.” Many drafts; few releases.

- Hard evidence gates for high-stakes claims.

- Red-team is non-optional for anything policy/finance-impacting.

- Consent is a first-class object (especially for community and Indigenous knowledge).

- Keep agents small and specialized; avoid a single “giant analyst” agent.

If you want, I can translate this into:

- a one-page architecture diagram (agents, flows, gates), and

- a starter “Agent Charter Pack” (one page per agent: mission, inputs/outputs, failure modes, evaluation metrics), aligned with your Epistemic Integrity Infrastructure.

A framework for a planetary intelligence commons

Below is a framework for a Planetary Intelligence Commons: an institutional and technical design for stewarding shared knowledge, models, and decision-support in ways that are legitimate, auditable, consent-respecting, and resilient against capture.

1) Definition and scope

Planetary Intelligence Commons (PIC):

A governed, open (but not indiscriminately public) socio-technical system that curates shared evidence, models, and deliberation processes to support the long-term habitability of Earth—across nested scales (planet → bioregion → watershed → neighborhood).

What the commons is not: a single global AI, a centralized “truth ministry,” or a data lake with no consent boundaries.

2) The three commons that must be co-governed

- Evidence Commons

- Observations, datasets, community knowledge, protocols, provenance metadata.

- Model Commons

- Forecasting and scenario models, causal graphs, assumptions, evaluation results, uncertainty characterizations.

- Deliberation Commons

- Participatory processes for interpreting evidence, negotiating tradeoffs, and deciding action—plus dispute resolution.

If any one of these is missing, “planetary intelligence” collapses into either technocracy (no legitimacy) or politics without grounding (no integrity).

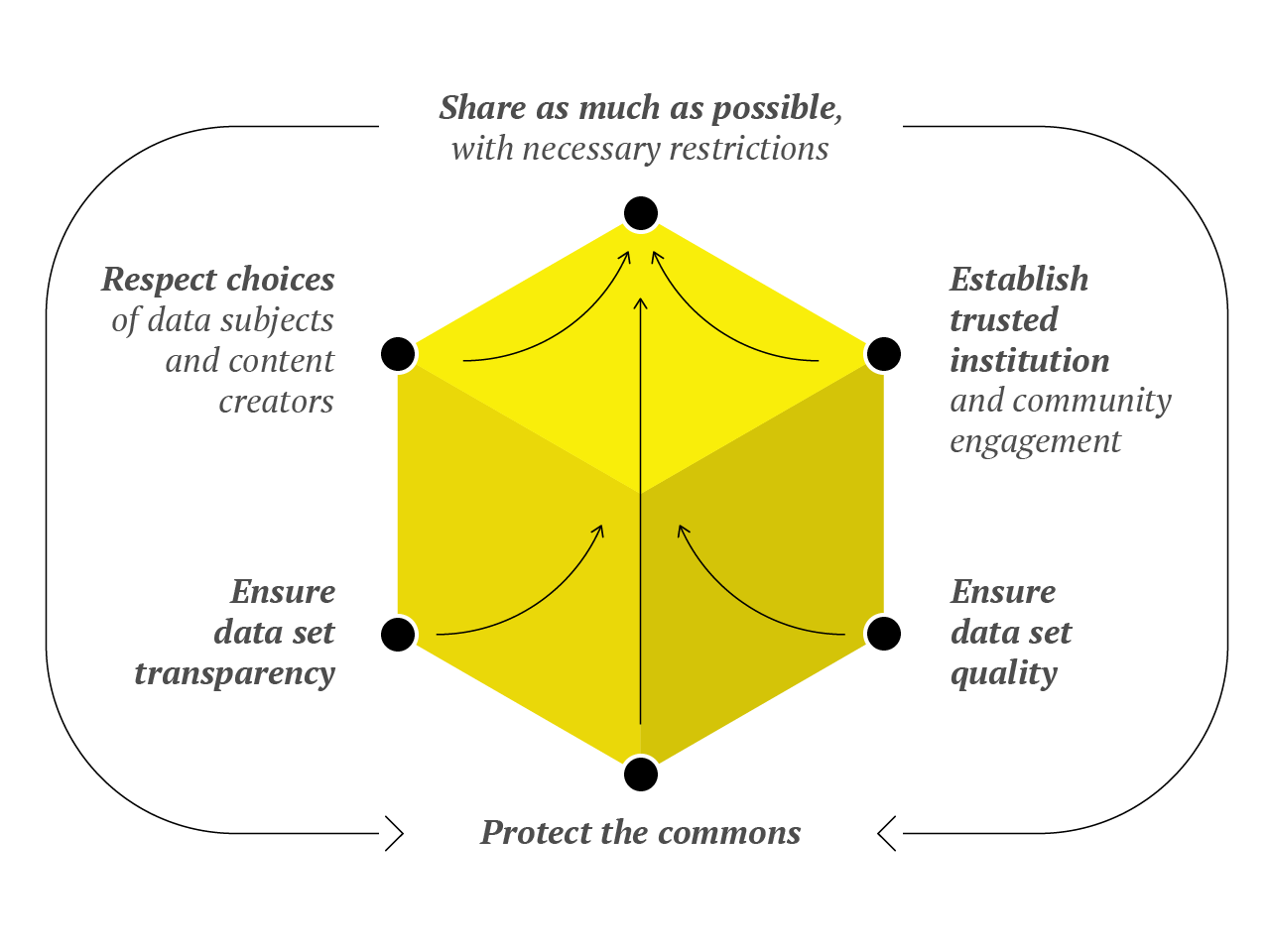

3) Core design principles

A. Epistemic integrity by design

All public-facing outputs must be traceable to:

- primary sources (or clearly labeled secondary synthesis)

- documented transformations (cleaning, aggregation, AI summarization)

- explicit assumptions and limitations

- known incentives/conflicts

- uncertainty bounds and confidence levels

- privacy/consent notes

B. Consent is a first-class constraint

Not all knowledge should be open. The commons must support:

- restricted access tiers

- revocable consent

- Indigenous data sovereignty and community ownership norms

- “do not train / do not publish” flags where appropriate

C. Subsidiarity and nesting

Decisions should be made at the lowest competent scale, with upward coordination for spillovers. Planetary governance must be nested, not monolithic.

D. Anti-capture and pluralism

The commons must resist domination by:

- vendors

- states

- philanthropies

- ideologies

- majoritarian bias that erases minority realities

Pluralism is not a moral luxury; it is a robustness requirement.

4) Governance architecture

A. Membership and boundaries

Define “who is in the commons” and “what resources are governed.”

- Membership classes: communities, scientists, civic institutions, NGOs, funders, agencies, auditors, tool providers

- Jurisdiction: planetary + bioregional nodes

- Resource boundaries: what evidence streams and models are covered

B. Roles (a minimal set)

- Stewards (Commons Council): set rules, approve indicators, enforce integrity policies

- Maintainers (Ops & Data Stewards): implement rules, manage infrastructure

- Contributors: submit data/models/claims under standards

- Auditors / Red Teams: independent review, stress-testing, misuse detection

- Ombuds / Mediators: handle disputes and harms

- End Users: communities, policymakers, practitioners

C. Decision rights

Use explicit “decision right tables,” e.g.:

- Who can add an indicator?

- Who can change a model?

- Who can publish a claim as “commons validated”?

- Who can revoke access due to consent violations?

D. Rule evolution (living constitution)

A commons must adapt. Provide:

- periodic rule review cycles

- amendment pathways

- emergency procedures (for crises, misinformation events, security breaches)

5) Operational rules: how knowledge becomes “commons-grade”

A. Contribution pipeline (from raw to validated)

- Submission (data / model / claim / narrative)

- Integrity check (provenance, licensing, consent, transformations)

- Peer review (domain reviewers + community reviewers where relevant)

- Adversarial audit (high-impact items)

- Publication (with versioning and uncertainty)

- Monitoring (post-release error reporting, drift detection)

- Revision or retraction (transparent, logged)

B. Claim labeling

Every published statement is labeled, e.g.:

- Observational (measured)

- Inferred (model-based)

- Scenario (conditional)

- Normative (value-based)

- Recommendation (policy/action)

- Speculative (hypothesis)

This prevents “model outputs” from laundering into “facts.”

6) Commons data and model standards

A. Evidence standards

- provenance metadata required

- unit consistency and methods documentation

- bias notes (sampling, instrument error, reporting bias)

- geospatial and temporal resolution standards

- data minimization (collect only what is needed)

B. Model standards (“Model Cards for the Commons”)

- intended use / prohibited use

- training/evaluation datasets (where applicable)

- known failure modes

- uncertainty reporting

- calibration evidence

- fairness and distributional impact analysis

- robustness under stress scenarios

C. Versioning and reproducibility

- immutable versions for citations

- reproducible pipelines (where feasible)

- “diffs” between versions

- rollback capability

7) Trust, legitimacy, and justice mechanisms

A. Community review and veto zones

For knowledge that affects specific communities:

- community review is mandatory

- consent and publication boundaries are enforceable

- “cultural harm” reporting pathways exist

B. Distributional impact requirement

Any major recommendation must include:

- who benefits / who bears costs

- who has agency in implementation

- how burdens are mitigated

- what reparative measures exist if harms occur

C. Conflict resolution

- lightweight mediation first

- formal arbitration next

- escalation paths for severe harm

- transparent outcomes and lessons learned

8) Incentives, funding, and anti-perverse incentives

A. Funding model (blended and diversified)

- public funding (infrastructure-grade)

- philanthropy (time-limited, non-controlling)

- membership dues (scaled)

- paid services that do not create pay-to-play truth

B. Contributor incentives

- reputation credits for high-quality contributions

- citations, badges, and “commons validation” marks

- microgrants for data collection and maintenance

- explicit penalties for low-integrity or manipulative submissions

C. Vendor neutrality

Tool vendors can participate, but:

- no exclusive control of infrastructure

- open interfaces and portability requirements

- transparency on model updates affecting outputs

9) Security and resilience

A. Threat model

- data poisoning

- coordinated misinformation

- model manipulation

- privacy leakage

- capture by powerful actors

- adversarial prompting and automated influence campaigns

B. Controls

- tiered access and sandboxing

- anomaly detection on contributions

- red-team drills

- incident response playbooks

- secure enclaves for sensitive datasets

- audit logs that are tamper-evident

10) The multi-agent “commons engine”

The commons operates day-to-day via a multi-agent workflow (human + AI):

- Integrity Agent enforces standards at intake

- Domain Agents produce analyses with uncertainty

- Red-Team Agent attacks weak claims

- Deliberation Agent generates decision briefs for councils and public forums

- Evaluation Agent tracks outcomes and model drift

- Stewardship Agent ensures consent and governance compliance

The key is separation of powers: generation, validation, publication, and governance should not be controlled by the same actor.

11) Minimal viable Planetary Intelligence Commons

If you want to start quickly without overbuilding:

MVP outputs (90 days):

- a public “commons charter” (rules, roles, rights, consent)

- a first indicator set (10–20 metrics) with provenance and uncertainty

- a contributions pipeline with integrity gates

- a dispute resolution process

- one pilot “bioregional node” connected to the planetary layer

MVP governance bodies:

- Commons Council (multi-stakeholder)

- Audit & Red Team panel

- Community Advisory circle (bioregional)

- Ombuds function

12) A concise charter template you can reuse

Planetary Intelligence Commons Charter (outline):

- Purpose and scope

- Membership and boundaries

- Rights and responsibilities

- Consent and privacy rules

- Evidence and model standards

- Contribution, review, and publication pipeline

- Labeling and uncertainty requirements

- Dispute resolution and harm reporting

- Anti-capture safeguards and conflicts of interest

- Security, incidents, and sanctions

- Funding and vendor neutrality

- Amendment process and review cycles

If you want to take this from framework to implementation, the next most useful artifact is a “PIC Charter v0.1” plus a one-page operating model (councils, pipelines, outputs) suitable for partners and funders. I can draft both in a form aligned with your Epistemic Integrity Infrastructure and your bioregional-first approach.

Please proceed

Below are two concrete artifacts you can use immediately with partners, funders, and collaborators:

- Planetary Intelligence Commons Charter v0.1 (governance + rules)

- One-Page Operating Model (how it actually runs day to day)

They are written to be bioregional-first, planetarily nestable, and explicitly aligned with epistemic integrity, consent, and anti-capture safeguards.

I. Planetary Intelligence Commons (PIC)

Charter v0.1

1. Purpose

The Planetary Intelligence Commons exists to steward shared evidence, models, and deliberative processes that support the long-term habitability of Earth, while respecting ecological limits, community sovereignty, and democratic legitimacy.

The Commons enables better questions, better decisions, and continuous learning across nested scales—from neighborhoods and bioregions to planetary systems.

2. Scope

The Commons governs three interdependent domains:

- Evidence Commons

Observations, datasets, community knowledge, monitoring protocols, and provenance metadata. - Model Commons

Forecasting models, scenario tools, causal maps, assumptions, uncertainty characterizations, and performance evaluations. - Deliberation Commons

Participatory processes, decision briefs, dispute resolution pathways, and records of reasoning behind collective choices.

3. Core Commitments

3.1 Epistemic Integrity

All published outputs must disclose:

- primary sources and dates

- transformations (cleaning, aggregation, AI summarization)

- assumptions and known limitations

- uncertainty and confidence levels

- known incentives or conflicts

- privacy and consent conditions

No unlabeled synthesis may circulate as “commons-validated.”

3.2 Consent and Knowledge Sovereignty

The Commons recognizes:

- community ownership of local knowledge

- Indigenous data sovereignty

- revocable consent

- restricted access tiers

- explicit “do not publish / do not train” flags

Open does not mean extractive.

3.3 Subsidiarity and Nesting

Decisions are made at the lowest competent scale, with coordination across scales for spillover effects.

Bioregional nodes are primary; planetary coordination is integrative, not directive.

3.4 Anti-Capture and Pluralism

The Commons is structured to prevent domination by:

- states

- corporations or vendors

- philanthropies

- ideological blocs

- technical elites

Pluralism is a robustness requirement, not an optional value.

4. Membership Classes

- Communities & Bioregional Councils

- Scientific & Technical Contributors

- Civic Institutions & Agencies

- Civil Society & NGOs

- Funders (non-controlling)

- Tool & Infrastructure Providers

- Independent Auditors & Red Teams

- Public Observers

Membership confers rights and responsibilities defined below.

5. Roles and Responsibilities

5.1 Commons Council (Stewards)

- Sets standards and indicators

- Approves governance changes

- Enforces integrity and consent rules

- Appoints auditors and ombuds

5.2 Maintainers (Operations & Data Stewards)

- Maintain infrastructure

- Implement standards

- Manage access and versioning

- Ensure security and continuity

5.3 Contributors

- Submit data, models, analyses, or narratives

- Comply with evidence and consent standards

- Accept review and revision requirements

5.4 Auditors / Red Teams

- Independently challenge high-impact claims

- Stress-test models and assumptions

- Detect misuse, bias, or manipulation

5.5 Ombuds / Mediators

- Receive harm reports

- Facilitate conflict resolution

- Recommend corrective action or sanctions

6. Contribution and Validation Pipeline

- Submission

Data, model, or claim submitted with required metadata. - Integrity Screening

Provenance, licensing, consent, and transformation checks. - Peer Review

Domain experts + affected community reviewers where relevant. - Adversarial Audit

Mandatory for policy- or finance-relevant outputs. - Publication

Versioned release with claim labels and uncertainty. - Monitoring

Post-publication error reporting and drift detection. - Revision or Retraction

Logged, transparent, and attributable.

7. Claim Labeling (Mandatory)

Every published statement must be labeled as:

- Observational

- Inferred (model-based)

- Scenario (conditional)

- Normative (value-based)

- Recommendation

- Speculative

This prevents the laundering of opinion or projection into fact.

8. Rights and Safeguards

- Right to explanation and traceability

- Right to contest and appeal

- Right to withdraw consent

- Protection for minority and dissenting views

- Prohibition on pay-to-validate influence

9. Funding and Independence

Permitted funding sources:

- public funding

- diversified philanthropy (non-controlling)

- membership dues (scaled)

- paid services that do not affect validation outcomes

No funder may control standards, conclusions, or publication.

10. Amendments and Review

- Annual governance review

- Emergency amendment pathway

- Supermajority requirement for core principles

- Public change logs

II. One-Page Operating Model

How the Planetary Intelligence Commons Actually Runs

1. Flow of Intelligence (End-to-End)

Signals → Evidence → Models → Questions → Deliberation → Decisions → Outcomes → Learning

Each step has a gate, an owner, and an audit trail.

2. The Commons Engine (Human + AI)

| Function | Who | Output |

|---|---|---|

| Integrity gate | Integrity agent + human steward | Admissible evidence |

| Analysis | Domain agents | Forecasts, scenarios |

| Challenge | Red-team agents | Failure modes |

| Sensemaking | Community agents | Value context |

| Deliberation | Facilitator agents + councils | Decision briefs |

| Evaluation | Learning agents | Performance metrics |

No single actor controls more than one critical function.

3. Decision Surfaces

The Commons does not decide for communities.

It produces decision-ready artifacts:

- trade-off maps

- uncertainty ranges

- distributional impacts

- policy and finance pathways

- “what would change our mind” criteria

Authority remains with legitimate local bodies.

4. Minimum Viable Outputs (First 90 Days)

- Commons Charter (this document)

- Integrity & consent standards

- 10–20 baseline indicators

- One bioregional pilot node

- Public questions backlog

- Dispute resolution process

5. What Makes This Different

- Questions are first-class outputs

- Uncertainty is explicit, not hidden

- Community knowledge is governed, not mined

- AI is separated into roles, not centralized

- Governance is nested, not globalized

This is intelligence with legitimacy, not optimization without consent.

Recommended Next Steps (Practical)

If you agree, the logical next moves are:

- PIC Charter v0.1 (public PDF)

Clean, branded, funder-ready version. - Bioregional Pilot Addendum

Applying the Charter to Genesee–Finger Lakes (or another region). - Agent Charter Pack

One page per agent: mission, inputs, outputs, failure modes. - Founding Partners Brief

A short invitation document for collaborators and funders.

I can draft these in sequence or in parallel. Please indicate which you would like to proceed with first.